TL;DR: the Paillier encryption scheme not only allows us to compute on encrypted data, it also provides an excellent illustration of modern security assumptions and a beautiful application of abstract algebra; in this first post we dig into the basics.

In this blog post series we walk through and explain Paillier encryption, a so called partially homomorphic encryption scheme first described by Pascal Paillier exactly 20 years ago. More advanced schemes have since been developed, allowing more operations to be performed on encrypted data, yet Paillier encryption remains relevant not only for understanding modern cryptography but also from a practical point of view, as illustrated recently by for instance Google’s Private Join and Compute or Snips’ Secure Distributed Aggregator.

Overview

Paillier is a public-key encryption scheme similar to RSA, where a keypair consisting of an encryption key ek and a decryption key dk is used to respectively encrypt a plaintext x into a ciphertext c, and decrypt a ciphertext c back into a plaintext x. The former is typically made publicly available to anyone, while the latter must be kept private by the key owner so that only they can decrypt. As we shall see, the encryption key also doubles as an evaluation key that allows anyone to compute on data while it remains encrypted.

The encryption function enc maps a plaintext x and randomness r into a ciphertext c = enc(ek, x, r), which we often write simply as enc(x, r) for brevity. Having the randomness means that we end up with different ciphertexts even if we encrypt the same plaintext several times: if r1 and r2 are different then so are c1 = enc(x, r1) and c2 = enc(x, r2) despite both of them being encryptions of x under the same encryption key.

This means that an adversary who obtains a ciphertext c cannot simply encrypt a plaintext and compare the result to c since this only works if they use the same randomness r. So as long as r remains unknown to the adversary, i.e. has a sufficiently high min-entropy from their perspective, then this strategy becomes impractical. Concretely, as we shall see below, for typical keypairs there are roughly 22048 (or approximately 10616) choices of r, meaning that every single plaintext x can be encrypted into that number of different ciphertexts.

To ensure high min-entropy of r, the Paillier scheme dictates that a fresh r is sampled uniformly and independently of x during every encryption and not used for anything else afterwards. More on this later, including the specific distribution used.

When r is chosen independently at random, Paillier encryption becomes what is known as a probabilistic encryption scheme, an often desirable property of encryption schemes per the discussion above.

Formally this makes Paillier a probabilistic encryption scheme, which is often a desirable property of encryption schemes.

As we shall see later, the underlying security assumptions also imply that it is impractical for an adversary to learn r given a ciphertext c.

In summary, the randomness prevents adversaries from performing brute-force attacks since they cannot efficiently check whether each “guess” was correct, even in situations where x is known to be from a very small set of possibilities, say x = 0 or x = 1. Of course, there may also be other ways for an adversary to check a guess, or more generally learn something about x or r from c, and we shall return to security of the scheme in much more detail later.

Below we will see concrete examples

Basic Operations

We first cover the basic operations that any public-key encryption scheme has: key generation, encryption, and decryption.

Key generation

The first step of generating a fresh Paillier keypair is to pick two primes p and q of the same length (like in RSA). For security reasons, each prime must be at least ~1000 bits so that their product is at least ~2000 bits.

class Keypair:

def __init__(self, p, q):

self.p = p

self.q = q

def generate_keypair(n_bitlength=2048):

p = sample_prime(n_bitlength // 2)

q = sample_prime(n_bitlength // 2)

return Keypair(p, q)

From this keypair, which must be kept private, we can derive both the private decryption key and the public encrypted key. The former is simply the two primes while the latter is essentially the product of them: n = p * q. One of the underlying security assumption is hence that while computing n from p and q is easy, computing p or q from n is hard.

Note that the encryption key is only based on n and not p nor q. The fact that it is easy to compute n from p and q, but believed hard to compute p or q from n, is the primary assumption underlying the security of the Paillier scheme (and of RSA).

def derive_encryption_key(keypair):

n = keypair.p * keypair.q

return EncryptionKey(n)

def derive_decryption_key(keypair):

p, q = keypair.p, keypair.q

return DecryptionKey(p, q)

We further explore the scheme’s security in part 3.

Encryption

While n fully defines the encryption key, for performance reasons it is interesting to keep a few extra values around in the in-memory representation. Concretely, for encryption keys we store not only n but also the derived nn = n * n and g = 1 + n, saving us from having to re-compute them every time they’re needed.

class EncryptionKey:

def __init__(self, n):

self.n = n

self.nn = n * n

self.g = 1 + n

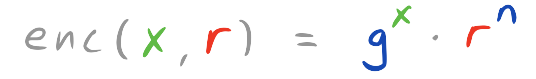

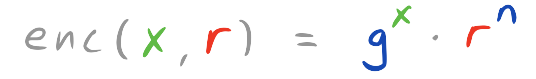

With this in place we can then express encryption. In mathematical terms this is done via the following equation:

that we can express in Python as follows:

def enc(ek, x, r):

gx = pow(ek.g, x, ek.nn)

rn = pow(r, ek.n, ek.nn)

c = (gx * rn) % ek.nn

return c

Note that we are doing all computations modulus nn = n * n. As we shall see below, many of the operations are done modulus nn, meaning arithmetic is done . This is critical for security and we shall return to it later.

However, it is already clear at this point that our ciphertexts become relatively large: since n is at least ~2000 bits then every ciphertext is at least ~4000 bits, even if we’re only encrypting a single bit! This blow-up is the main reason why Paillier encryption is computationally expensive since arithmetic on numbers this large is significantly more expensive than the native arithmetic on e.g. 64 bits numbers.

Before we can test the code above we also need to known how to generate the randomness r. This is done by sampling from the uniform distribution over numbers 0, ..., n - 1, with the condition that the value is co-prime with n, i.e. that gcd(r, n) == 1. We can do this efficiently by first sampling a random number below n and then use the Euclidean algorithm to verify that it is co-prime; if not we simply try again.

def generate_randomness(ek):

while True:

r = secrets.randbelow(ek.n)

if gcd(r, ek.n) == 1:

return r

As it turns out, one loop iteration is almost always enough, to the point where we can realistically skip the co-prime check altogether. More on this in part 2.

Decryption

Turning next to decryption, again we start out by caching a few values derived from p and q. Note that we really only need the order of n, i.e. (p - 1) * (q - 1), but in part 2 we will have additional uses of them.

class DecryptionKey:

def __init__(self, p, q):

n = p * q

self.n = n

self.nn = n * n

self.g = 1 + n

order_of_n = (p - 1) * (q - 1)

# for decryption

self.d1 = order_of_n

self.d2 = inverse(order_of_n, n)

# for extraction

self.e = inverse(n, order_of_n)

Decryption is then done as shown in the following code; we will explain why this recovers the plaintext in part 3.

def dec(dk, c):

gxd = pow(c, dk.d1, dk.nn)

xd = dlog(gxd, dk.n)

x = (xd * dk.d2) % dk.n

return x

Finally, Paillier supports an additional operation that is not always available in a public-key encryption scheme: the complete reversal of encryption into both the plaintext and the randomness.

def extract(dk, c):

rn = c % dk.n

r = pow(rn, dk.e, dk.n)

return r

When the scheme was first published this was mentioned as an interesting property on its own, but later literature have had less focus on this. As we see in part 4, one particular application that is still relevant is that it can serve as a simple proof that decryption was done correctly: if someone asks the key owner to decrypt a ciphertext c, and the key owner returns both plaintext x and randomness r, then it is easy to verify that indeed c == enc(ek, x, r).

Homomorphic Operations

The most attractive feature of the Paillier scheme is that it allows us to compute on data while it remains encrypted: given ciphertexts c1 and c2 encrypting respectively x1 and x2, it is possible to compute a ciphertext c encrypting x1 + x2 without knowing the decryption key or in other ways learn anything about x1, x2, and x1 + x2.

This opens up for very powerful applications, including electronic voting, secure auctions, private-preserving machine learning, and even general purpose secure computation. We go through some of these in more detail in part 4.

Addition

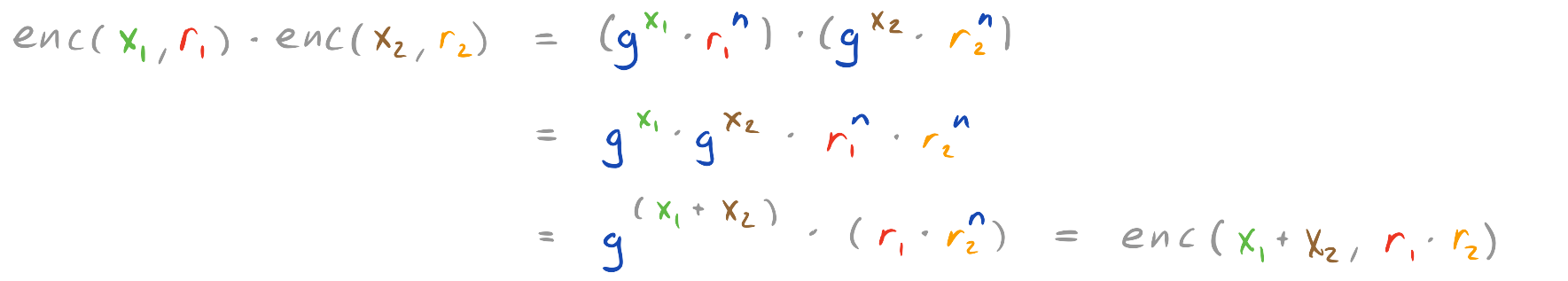

Let us first see how one can do the above and compute the addition of two encrypted values, say c1 = enc(ek, x1, r1) and c2 = enc(ek, x2, r2).

To do this we multiply the two ciphertexts, letting c = c1 * c2. To see that this indeed gives us what we want, we plug in our formula for encryption and get the following:

In other words, if we multiply ciphertext values c1 and c2 then we get exactly the same result as if we had encrypted x1 + x2 using randomness r1 * r2!

def add_cipher(ek, c1, c2):

c = (c1 * c2) % ek.nn

return c

Note that add_cipher can also be used to compute the addition of a ciphertext and a plaintext value, by first encrypting the latter. In this particular case we might as well use 1 as randomness when encrypting the plaintext value as shown in add_plain.

def add_plain(ek, c1, x2):

c2 = enc(ek, x2, 1)

c = add_cipher(ek, c1, c2)

return c

We now know how to add encrypted values together without decrypting anything! Note however, that the resulting ciphertexts have a slightly different form than freshly generated ones, with a randomness that is no longer a uniformly random value but rather a composite such as r1 * r2. This does not affect correctness nor the ability to decrypt, but in some applications it may leak extra information to an adversary and hence have consequences for security. We return to this issue below after having introduced more operations.

Subtraction

Subtraction follows easily from addition given negation functions.

def neg_cipher(ek, c):

return inverse(c, ek.nn)

def neg_plain(ek, x):

return ek.n - x

The former computes the multiplicative inverse and the latter the additive inverse, which simply means that c * neg_cipher(c) == 1 modulus nn, and x + neg_plain(x) == 0 modulus n. This basically allows us to turn x1 - x2 into x1 + (-x2) and use the addition operations from earlier.

def sub_cipher(ek, c1, c2):

minus_c2 = neg_cipher(ek, c2)

c = add_cipher(ek, c1, minus_c2)

return c

def sub_plain(ek, c1, x2):

minus_x2 = neg_plain(ek, x2)

c = add_plain(ek, c1, minus_x2)

return c

Note that the resulting ciphertexts again have a slightly different form than freshly encrypted ones, namely r1 * r2^-1.

Multiplication

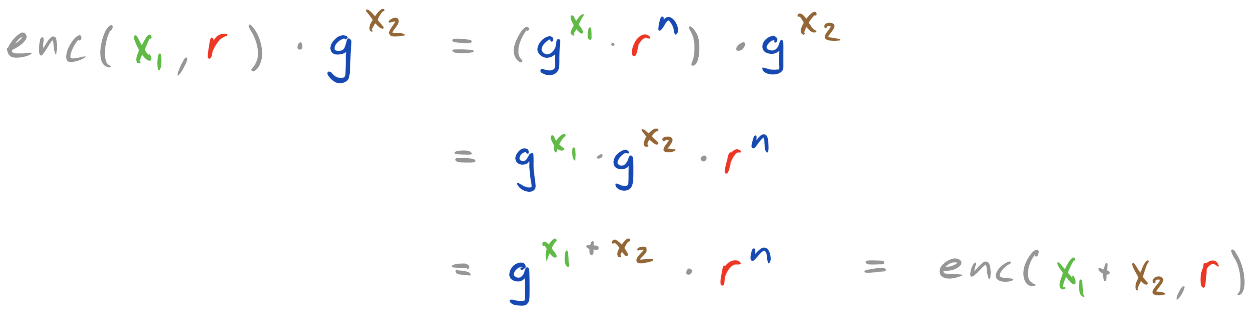

The final operation supported by Paillier encryption is multiplication between a ciphertext and a plaintext. The fact that it is not known how to compute the multiplication of two encrypted values is what makes it a partially homomorphic scheme, and is what sets it apart from more recent somewhat homomorphic and fully homomorphic schemes where this is indeed possible.

Given c = enc(x, r) and a k we compute c^k = (g^x * r^n) ^ k == g^(x * k) * (r^k)^n == enc(x * k, r ^ k).

def mul_plain(ek, c1, x2):

c = pow(c1, x2, ek.nn)

return c

Note that More precisely, non-interactive multiplication is not possible, but instead only by running a small protocol between the key owner and the evaluator.

Linear functions

Combining the operations above we can derive a function linear for evaluating e.g. the dot product between a vector of ciphertexts and a vector of plaintexts.

def linear(ek, cs, xs):

terms = [

mul_plain(ek, c, x)

for c, x in zip(cs, xs)

]

adder = lambda c1, c2: add_cipher(ek, c1, c2)

return reduce(adder, terms)

As an example, this allows us to express the following:

cs = [enc(ek, 1), enc(ek, 2), enc(ek, 3)]

xs = [10, -20, 30]

c = linear(ek, cs, xs)

assert dec(dk, c) == (1 * 10) - (2 * 20) + (3 * 30)

and captures everything we can do with encrypted values in the Paillier scheme, with e.g. add_cipher(c1, c2) being essentially the same as linear([c1, c2], [1, 1]), sub_cipher(c1, c2) the same as linear([c1, c2], [1, -1]), and mul_plain(c, x) the same as linear([c], [x]).

Re-randomization

As noted throughout, the ciphertexts resulting from homomorphic operations have randomness components with a structure that differs from the one found in freshly generated ciphertexts. In some cases, taking this into account may simply make analyzing the security of the system harder; in others, it may even leak something to an adversary about the encrypted values.

A freshly generated ciphertext will have a randomness component that was independently sampled …..

TODO: good examples of the above?

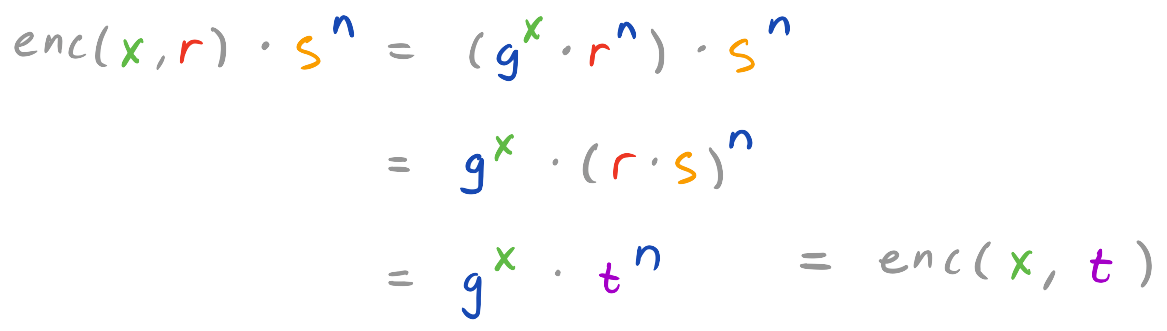

Fortunately, we can easily define a re-randomize operation that makes any ciphertext look exactly like a freshly generated one, effectively erasing everything about how it was created. To do this we have to make sure the randomness component looks uniformly random given anything that the adversary may know. To do this we simply add a fresh encryption of zero enc(0, s), which for enc(x, r) will give us an encryption enc(x, r*s); however, if s is independent and uniformly random then so is r*s. We are essentially

def rerandomize(ek, c, s):

sn = pow(s, ek.n, ek.nn)

d = (c * sn) % ek.nn

return d

could be done lazily

Next Steps

In the next post we will look at concrete applications of Paillier encryption, in particular when it comes to privacy-preserving machine learning.

Dump

while r is limited to those numbers in Zn that have a multiplication inverse, which we denote as Zn*.

To fully define this mapping we note that x can be any value from Zn = {0, 1, ..., n-1} while r is limited to those numbers in Zn that have a multiplication inverse, i.e. Zn*; together this implies that c is a value in Zn^2*, ie. amoung the values in {0, 1, ..., n^2 - 1} that have multiplication inverses. Finally, n = p * q is a typical RSA modulus consisting of two primes p and q, and g is a fixed generator, typically picked as g = 1 + n.

, as well as its inverse dec that recovers both x and r from a ciphertext. Here, enc is implicitly using a public encryption key ek that everyone can know while dec is using a private decryption key dk that only those allowed to decrypt should know.

Let us take a closer look at that (the use of randomness), and plot where encryptions of zero lies.