TL;DR: In this series of blog posts we go through how modern cryptography can be used to perform secure aggregation for private analytics and federated learning. As we will see, the right approach depends on the concrete scenario, and in this first part we start with the simpler case consisting of a network of stable parties.

Motivation

(coming …)

Federated Learning

Analytics and statistics

Secure aggregation

From the above use-cases we are going to focus on the problem of aggregating large vectors held by a set of users such that an intended recipient learns their weighted sum yet the individual vectors remain private. For our running example we are concretely going to assume three users.

users = [

User('user1'),

User('user2'),

User('user3'),

]

output_receiver = OutputReceiver()

Note that the weighted sum inherently reveals something about the inputs, namely that which can be derived from it. For instance, by learning that a sum taking using equal weights is e.g. 150, one also learns that someone had an input that was at most 150/3 == 50. Mitigating this type of leakage requires additional techniques such as differential privacy.

The Insecure Solution

No cryptography used. Single trusted aggregator.

Distributing Trust

Introduce more aggregators and distribute trust between them.

Our starting point is a simple solution based on additive secret sharing. Recall that in this scheme, a secret is split into a number of shares in such a way that if you have less than all shares then nothing is leaked about the secret, yet if you have all then the secret can be reconstructed. As seen below, this is achieved by letting all but one share be independently random values, and using the sum of these to blind the secret as the final share (essentially forming a one-time pad encryption of the secret). To reconstruct you simply sum all shares together.

def share(secret, number_of_shares):

random_shares = [

sample_randomness(secret.shape)

for _ in range(number_of_shares - 1)

]

missing_share = (secret - sum(random_shares)) % Q

return [missing_share] + random_shares

def reconstruct(shares):

secret = sum(shares) % Q

return secret

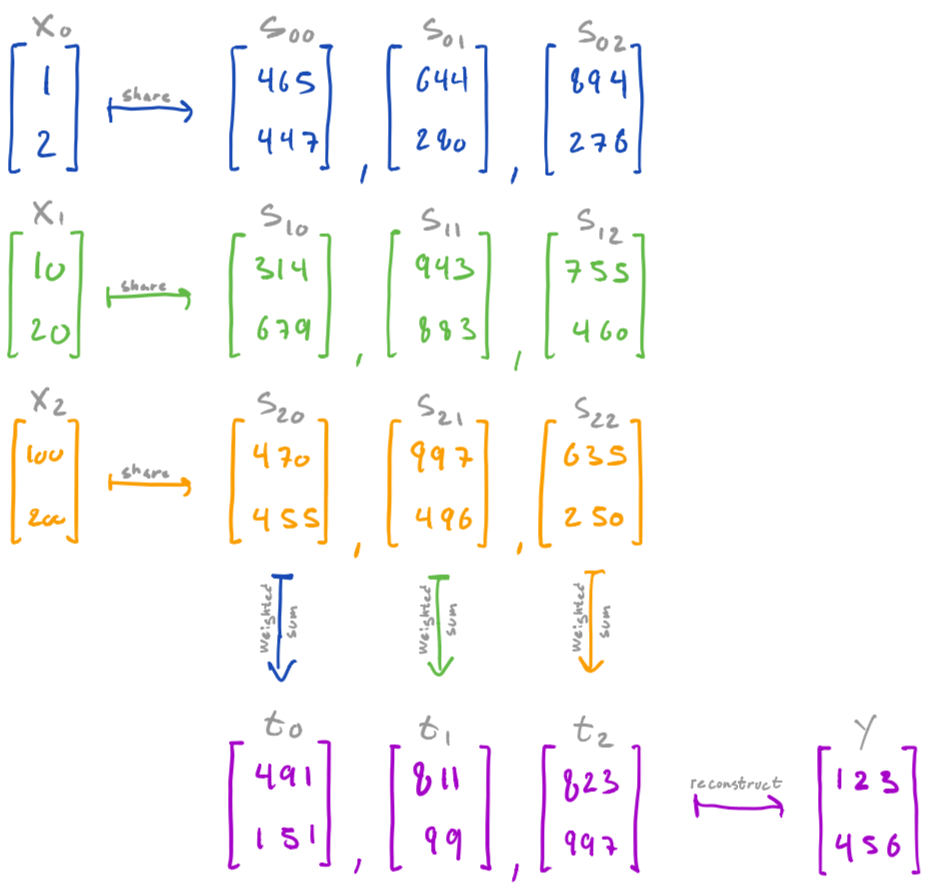

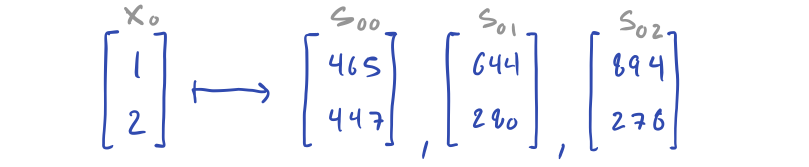

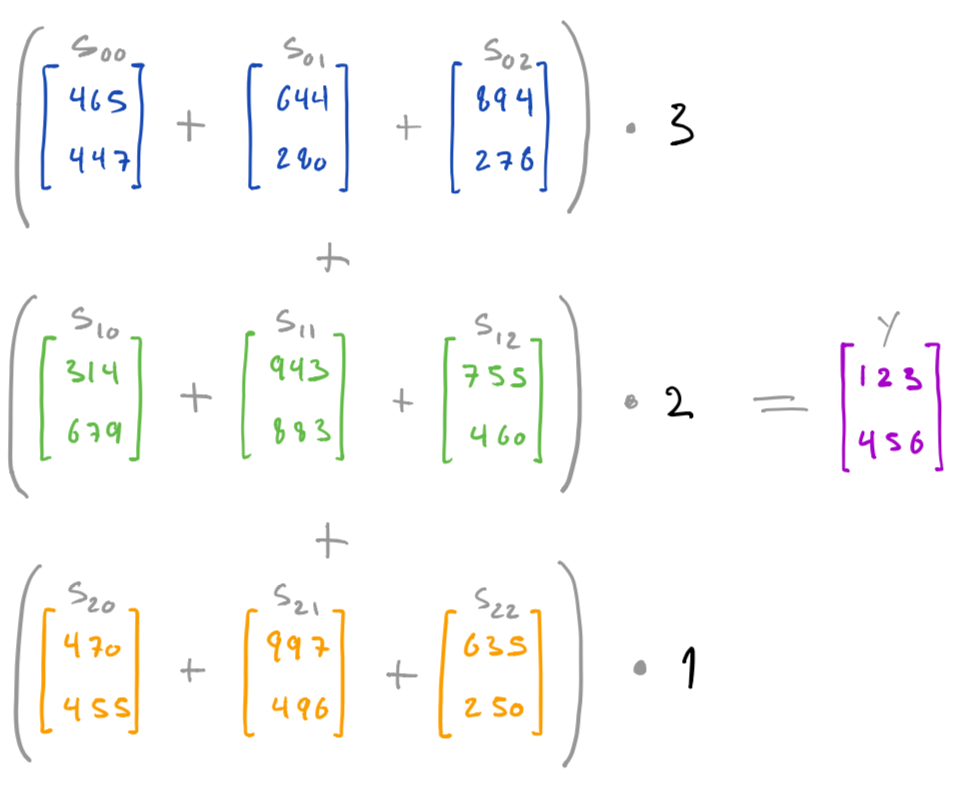

For instance, secret x0 may be shared into [s00, s01, s02], where s00 is the blinded secret, and s01 and s02 are randomly sampled. Concretely, if x0 is the vector [1, 2] then we might share that into the following three vectors.

We also take advantage of the fact that the scheme allows us to compute on secret values by computing on the shares, i.e. while they remain encrypted. In particular, that we can compute a weighted sum of secret values by computing a weighted sum over each corresponding set of shares.

def weighted_sum(shares, weights):

shares_as_matrix = np.stack(shares, axis=1)

return np.dot(shares_as_matrix, weights) % Q

For instance, say we have shared three secrets x0, x1, and x2:

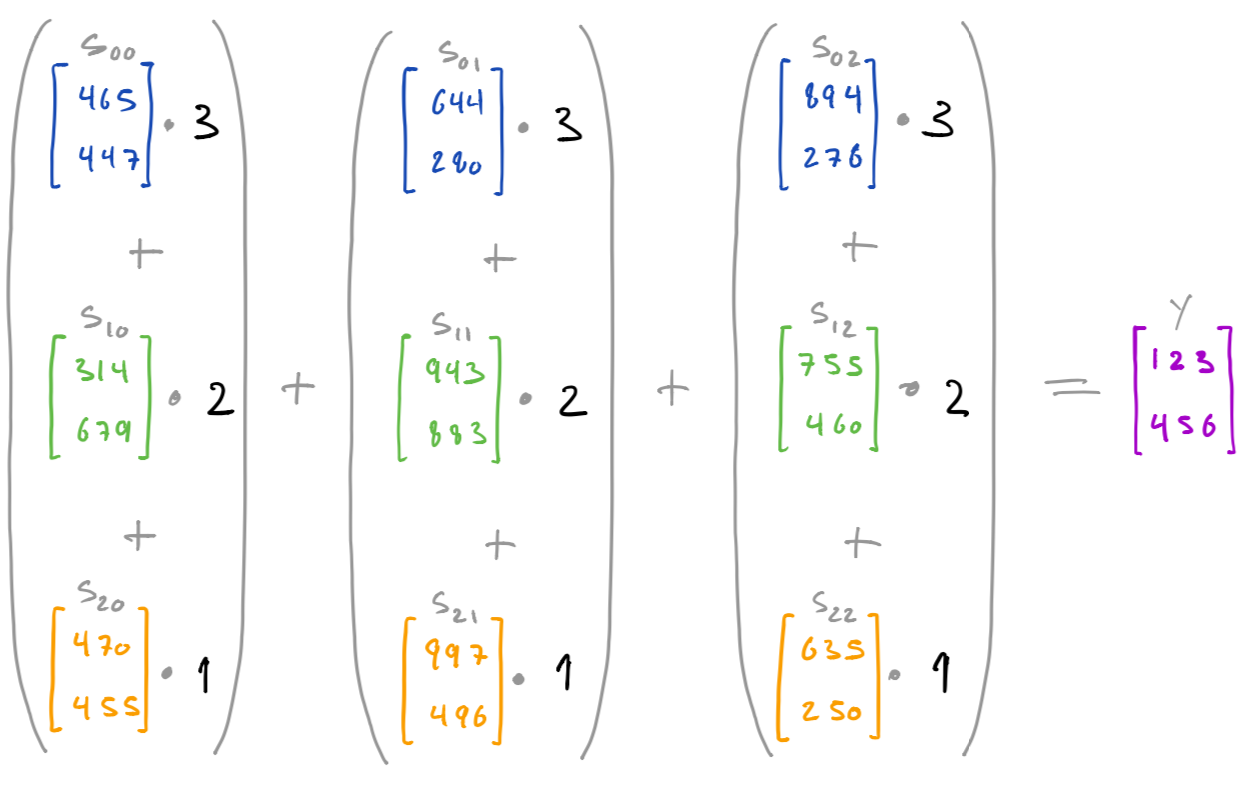

By computing a weighted sum over each set of shares:

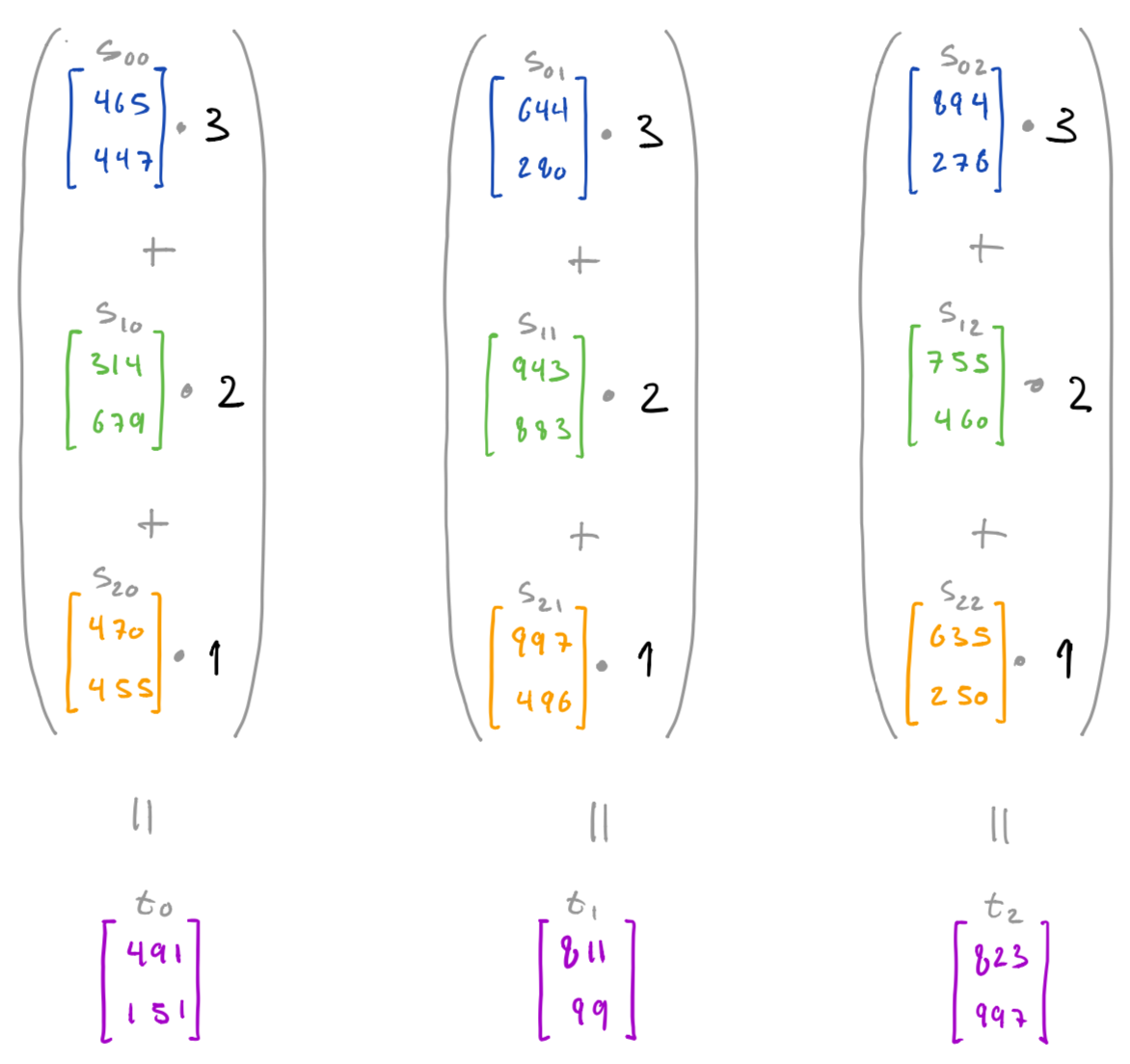

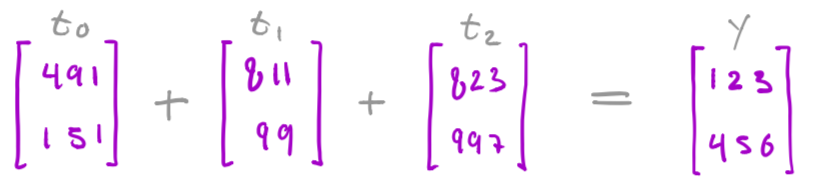

we then end up with shares t0, t1, and t2 of the weighted sum (x0 * w0) + (x1 * w1) + (x2 * w2):

For simplicity we here assume three data owners, but the same approach works for any number of owners.

TODO figure with owners and x

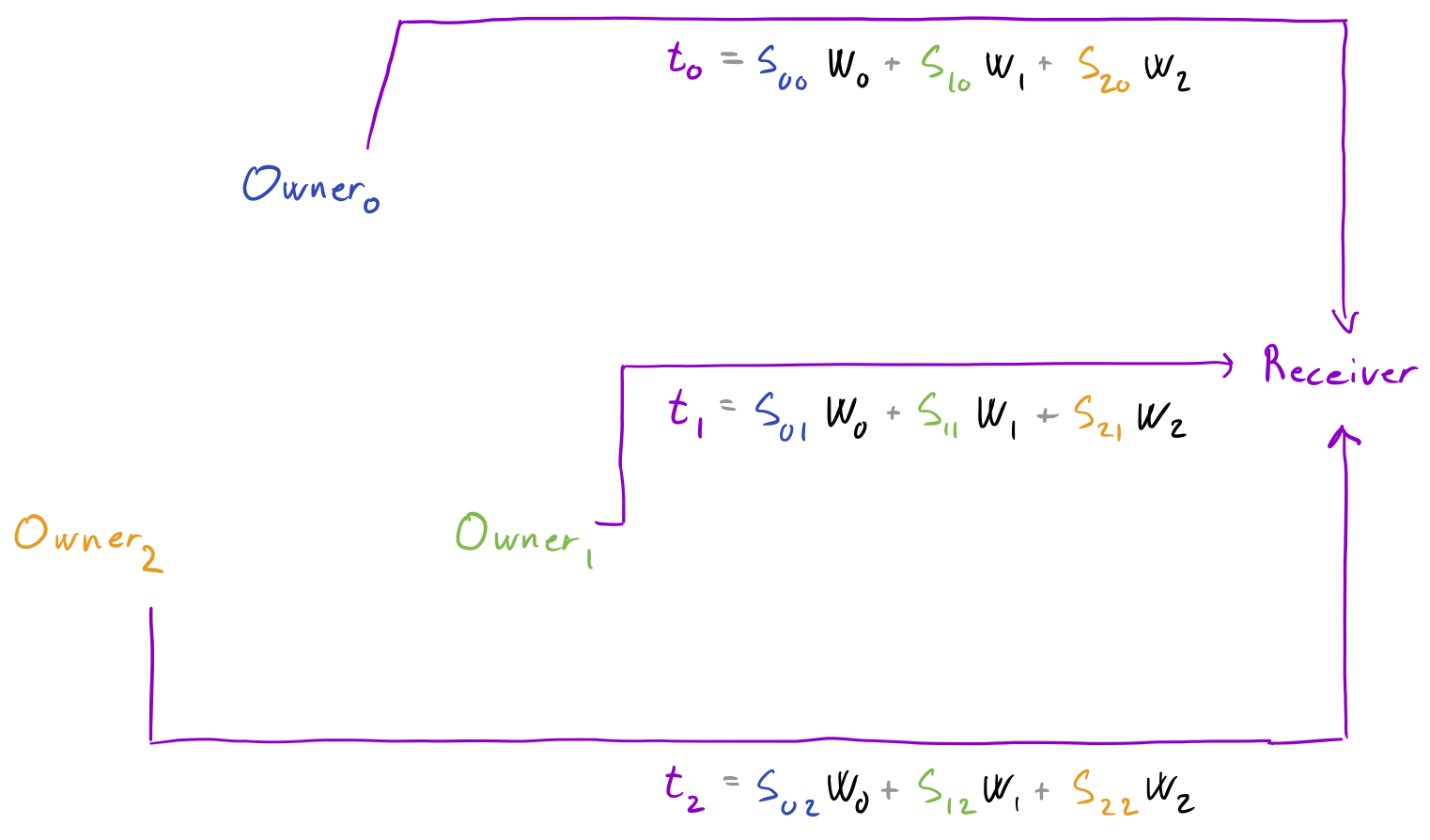

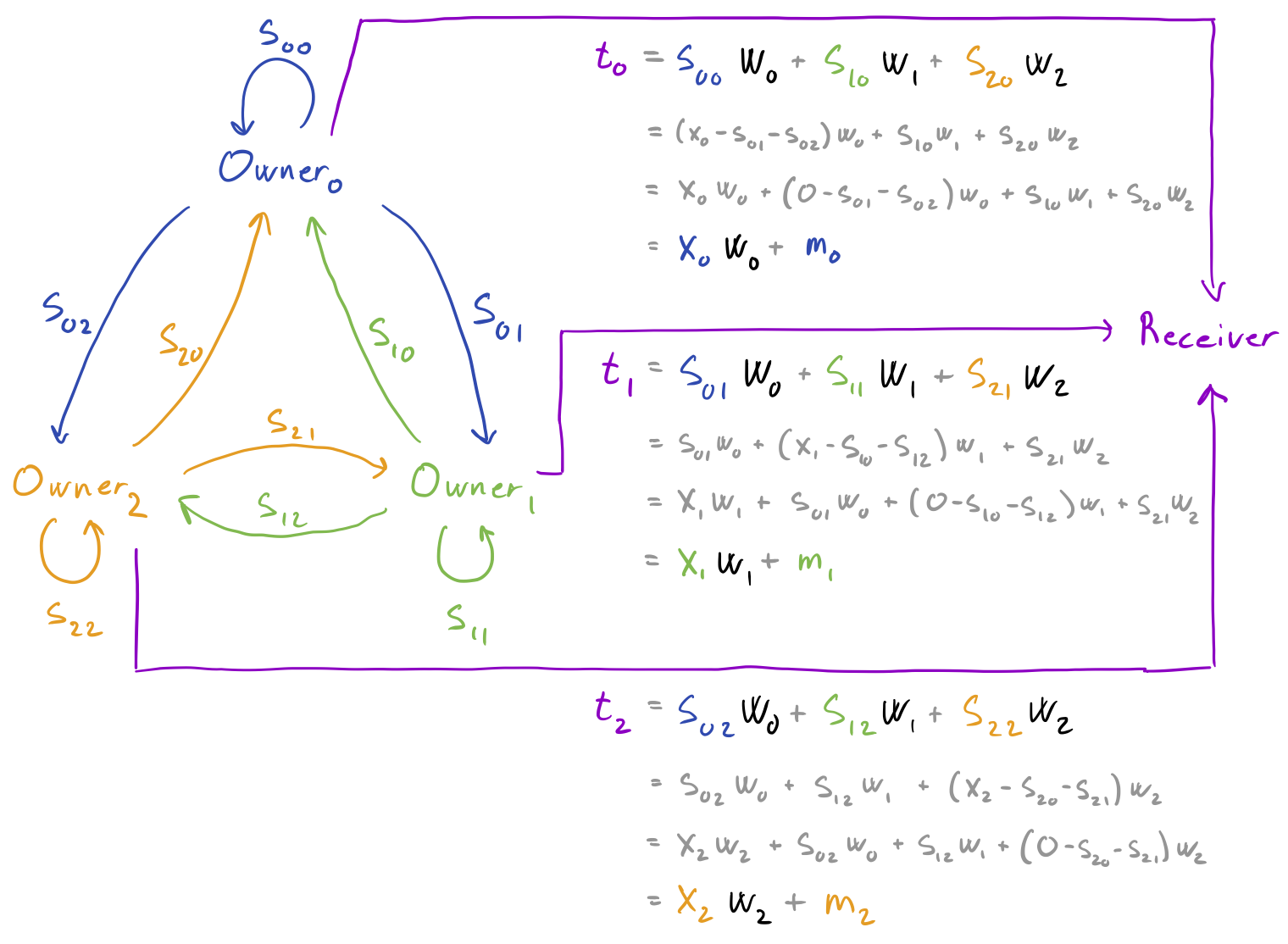

In the first step, each data owner secret shares its input and sends a share to each of the other owners (including keeping one for itself).

Once all shares have been distributed, i.e. every owner has a share from every other owner, they each compute a weighted sum. These sums are in fact shares of the output, which they send to the output receiver.

Finally, having received a share from every owner, the output receiver can reconstruct to learn the result.

TODO figure with y = t0 + t1 + t2

In code the above steps are as follows:

# step 1

for x, owner in zip(inputs, data_owners):

owner.distribute_shares_of_input(x, data_owners)

# step 2

for owner in data_owners:

owner.aggregate_and_send_share_of_output(weights, output_receiver)

# step 3

output = output_receiver.reconstruct_output()

where data_owners and output_receiver are instances of the following classes:

def distribute_shares_of_input(user, x, aggregators):

shares_of_input = share(x, len(aggregators))

user.send('input_shares', {

aggregator: share

for aggregator, share in zip(aggregators, shares_of_input)

})

def aggregate_and_send_share_of_output(aggregator, weights, output_receiver):

shares_to_aggregate = aggregator.receive('input_shares')

share_of_output = weighted_sum(shares_to_aggregate, weights)

aggregator.send('output_shares', {

output_receiver: share_of_output

})

def reconstruct_output(output_receiver):

shares_of_output = output_receiver.receive('output_shares')

output = additive_reconstruct(shares_of_output)

return output

The security of this approach follows directly from the secret sharing scheme: no owner has enough shares to reconstruct neither the inputs nor the output, and the output receiver only sees shares of the output. In fact, because we are using a scheme with a privacy threshold of n - 1, this holds even if all players except one are colluding, meaning each data owner only has to trust itself.

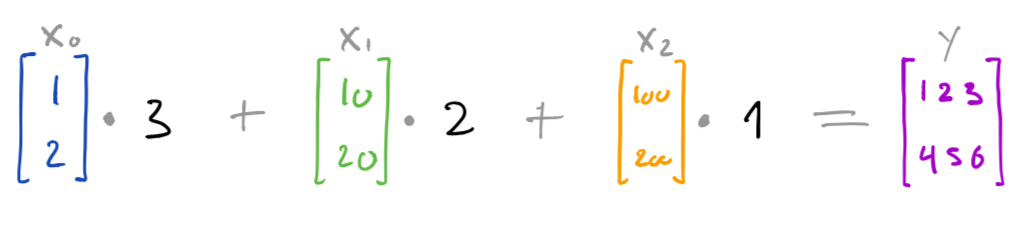

A concrete example

We can look at a concrete execution to better see how and why this works. Here, the inputs of the data owners are [1, 2], [10, 20], and [100, 200] respectively, and the weights are [3, 2, 1]. This means that our expected result is [1*3 + 10*2 + 100*1, 2*3 + 20*2 + 200*1] == [123, 246].

In the first step, each data owner shares its input vector into three random vectors, resulting in an imaginary (3, 3, 2) tensor s. For instance, sharing x0 results in s00, s01, and s02 where s00 + s01 + s02 == x0 (modulus Q).

In the next step, each owner then computes a weighted sum across one of the three columns, resulting in three new vectors t0, t1, and t2.

In the final step these three vectors are added together by the output receiver.

While this protocol already offers good performance, it can also be significantly optimized if we are willing to make some assumptions about the scenario in which it is used and the reliability of the parties involved. In particular, in the following sections we shall see how communication can be reduced significantly if it is repeatedly executed by the same parties.

this is typically a good solution when the aggregate happens between a few data owners connected on reilable high-speed networks

gives high security since each data owner only has to trust themselves

it unfortunately also has a serious problem if we were to use it across e.g. the internet, where users are somewhat sporadic. In particular, the distribution of shares represents a significant synchronization point between all users, where even a single one of them can bring the protocol to a halt by failing to send their shares.

The Basic Idea

Say our goal is to compute y as defined by following expression, i.e. as the weighted sum of vectors x0, x1, x2 using weights 3, 2, 1 respectively:

This can be done by the following

In the next section it will become obvious why one would do so, you could replace

cd

cdscd

cdscds

cdscds

Optimizing For Server Setting

Zero Masking

def additive_share(secret, number_of_shares, index_of_masked_secret=0):

shares = [

sample_randomness(secret.shape)

for _ in range(number_of_shares - 1)

]

masked_secret = (secret - sum(shares)) % Q

return shares[:index_of_masked_secret] + \

[masked_secret] + \

shares[index_of_masked_secret:]

class DataOwner(Player):

def distribute_shares_of_zero(self, input_shape, players):

shares_of_zero = additive_share(

secret=np.zeros(shape=input_shape, dtype=int),

number_of_shared=len(players),

)

self.send('zero_shares', {

player: share

for player, share in zip(players, shares_of_zero)

})

def combine_shares_of_zero_and_send_masked_input(self, x, w, output_receiver):

shares_to_combine = self.receive('zero_shares')

share_of_zero = additive_sum(shares_to_combine)

mask = share_of_zero

x_masked = ((x * w) + mask) % Q

self.send('output_shares', {

output_receiver: x_masked

})

Pre-computing masks

class DataOwner(Player):

pregenerated_masks = []

#

# for offline phase

#

def distribute_shares_of_zero(self, input_shape, players):

# (unchanged ...)

def combine_shares_of_zero(self):

shares_to_combine = self.receive('zero_shares')

share_of_zero = additive_sum(shares_to_combine)

mask = share_of_zero

self.pregenerated_masks.append(mask)

#

# for online phase

#

def next_mask(self):

return self.pregenerated_masks.pop(0)

def send_masked_input(self, x, w, output_receiver):

mask = self.next_mask()

x_masked = ((x * w) + mask) % Q

self.send('output_shares', {

output_receiver: x_masked

})

zero-sharing

To some extend this is the basis of Google’s approach, where thet pick a subsample of data owners and add recovery mechanism

https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/281 Google’s Approach: https://acmccs.github.io/papers/p1175-bonawitzA.pdf

Correlated randomness, Google’s approach, and sensor networks

Fully decentralized can be broken into offline and online phase, where shares of zero are first generated by the users. This is essentially the basis of the Google protocol. One problem is if some users drop out between the two phases, and the Google protocol extends the basic idea to mitigate that issue. From an operational perspective they also keep the iterations very short, and only aggregate when phones are most stable (plugged and on wifi).

Seeding

One rule of thumb in secure computation is to never sample and send large random values, but to sample and send a random seed instead. Since seeds are typically much smaller than the random values they are expanded into, this can potentially save a significant amount on communication cost at the expense of a bit of cheap computation on both the sender and the receiver (i.e. the usual space-time tradeoff). This applies very nicely to our use case since all shares except one are just random values that can hence be replaced with seeds.

Before adapting our protocol to take advantage of seeds, we first need to address one small caveat; namely, that the expanded values are now technically only pseudo-random with the risk of having an impact on the security of the protocol. However, at long as we make sure to expand the seeds using a pseudo-random generator (PRG) that is cryptographically strong then this is not an issue for all practical purposes. In fact, it is likely to be exactly how the operation system sample random values for you behind the scenes anyway.

SEED_BITLENGTH = 80

S = 2**SEED_BITLENGTH

class Seed:

def __init__(self, value, shape):

self.value = value

self.shape = shape

def sample_seed(shape):

value = secrets.randbelow(S)

return Seed(value, shape)

def expand_seed(seed):

# TODO replace with secure expansion

size = np.prod(seed.shape)

random.seed(seed.value)

randomness = [random.randrange(Q) for _ in range(size)]

return np.array(randomness).reshape(seed.shape)

def expand_seeds_as_needed(values):

expanded = [

expand_seed(value) if isinstance(value, Seed) else value

for value in values

]

return expanded

def additive_share_with_seeds(secret, number_of_shares, index_of_masked_secret=0):

shares = [

sample_seed(secret.shape)

for _ in range(number_of_shares - 1)

]

masked_secret = (secret - sum(expand_seeds_as_needed(shares))) % Q

return shares[:index_of_masked_secret] + \

[masked_secret] + \

shares[index_of_masked_secret:]

More concretely, when the zero masks are being generated, that each data owner keeps for itself …

class DataOwner(Player):

pregenerated_masks = []

#

# offline phase

#

def distribute_shares_of_zero(self, input_shape, players):

shares_of_zero = additive_share_with_seeds(

secret=np.zeros(shape=input_shape, dtype=int),

number_of_shares=len(players),

index_of_masked_secret=index_in_list(self, players),

)

self.send('zero_shares', {

player: share

for player, share in zip(players, shares_of_zero)

})

def combine_shares_of_zero(self):

shares_to_combine = self.receive('zero_shares')

shares_to_combine = expand_seeds_as_needed(shares_to_combine)

share_of_zero = additive_sum(shares_to_combine)

mask = share_of_zero

self.pregenerated_masks.append(mask)

#

# online phase

#

def next_mask(self):

# (unchanged ...)

def send_masked_input(self, x, w, output_receiver):

# (unchanged ...)

This is a significant improvement for applications dealing with very large vectors, as we have brought the overhead of secure aggregation close to that of (insecure) aggregation: the only additional communication is for the seeds, so if the vectors are large then this become negligible.

Moreover, if is it reasonable in the specific application to make the assumption that the same set of data owners will repeatedly make many aggregations, then the fact that we can pre-generate masks puts us in an even better situation. However, in that case we can actually do even better still.

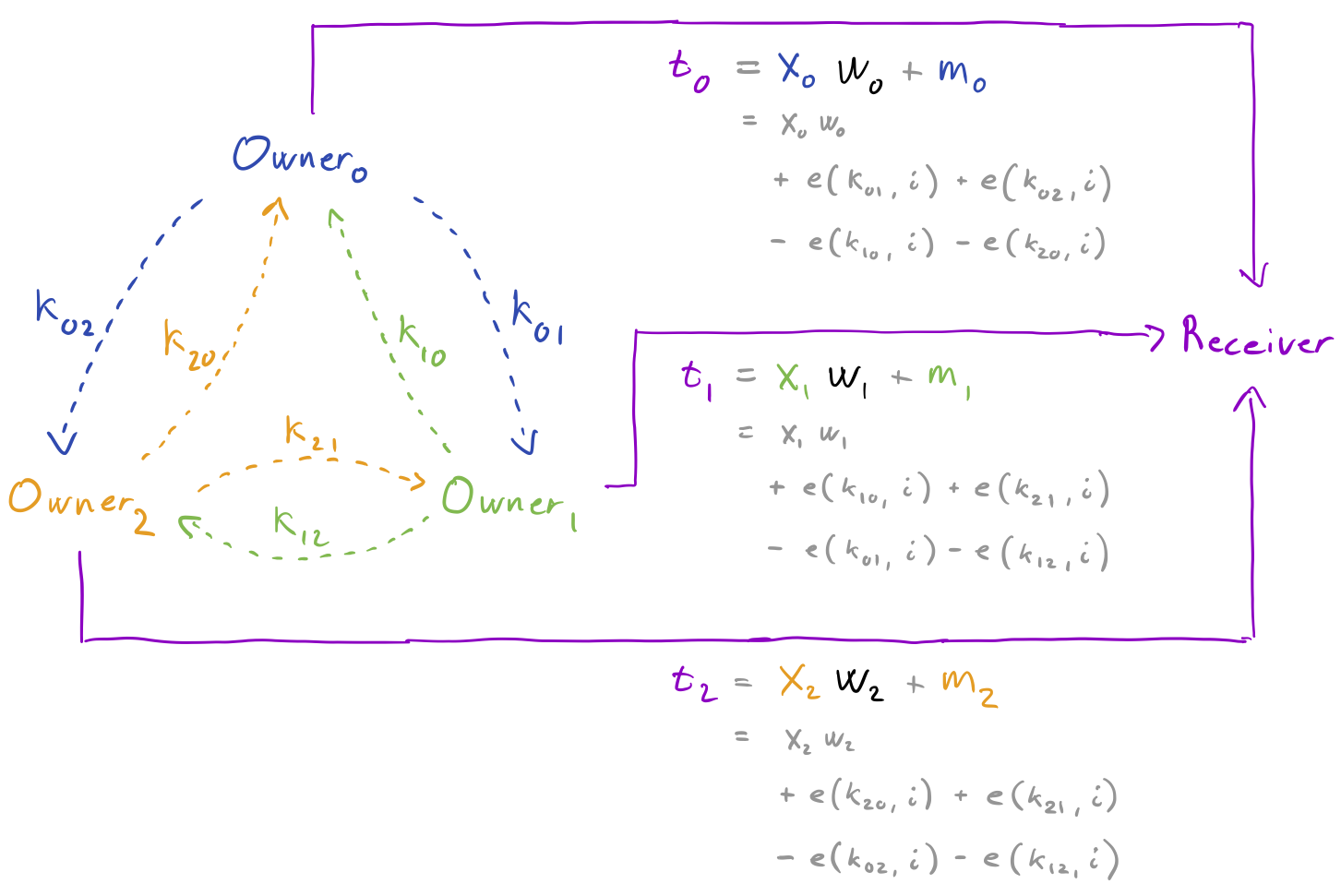

Keyed seeding

Above we were expanding a small random seed into a much larger value that from all practical purposes looked entirely random. However, we still had to rely on communication a small amount of random bits for every single mask. However, another cryptographic primitive called pseudorandom functions (PRF) allows us to essentially re-use these random bits for many masks, giving an advantage in the cases where the same set of data owners are in repeated need of masks. ChaCha20 is one such function, yet for the purpose of this blog post we continue to …

The overall flow in the protocol looks the same, yet now the exchange between the owners for mask generation is replaced by a much rarer key setup. This process simply sees each owner sampling and distributing fresh keys, which are stored for future use. In particular, by giving these keys to a PRF together with an iteration number i, fresh masks can be generated and used for masks: e(k, i).

class DataOwner(Player):

iteration = 0

keys_to_add = []

keys_to_sub = []

#

# setup phase

#

def distribute_keys(self, players):

self.keys_to_add = sample_keys(

number_of_keys=len(players),

index_of_missing_key=index_in_list(self, players),

)

self.send('keys', {

player: share

for player, share in zip(players, self.keys_to_add)

})

def gather_keys(self):

self.keys_to_sub = self.receive('keys')

#

# online phase

#

def next_mask(self, shape):

this_iteration = self.iteration

self.iteration += 1

masks_to_add = [

sample_keyed_mask(key, this_iteration, shape)

for key in self.keys_to_add if key is not None

]

masks_to_sub = [

sample_keyed_mask(key, this_iteration, shape)

for key in self.keys_to_sub if key is not None

]

mask = (sum(masks_to_add) - sum(masks_to_sub)) % Q

return mask

def send_masked_input(self, x, w, output_receiver):

# (unchanged ...)

Next Steps

we could have gone directly to the final solution but this detour showed how game-based security proofs work…

Scaling to many users and dealing with sporadic behaviour.

Abstract properties

all the operations we have used can be expressed as abstract properties of the secret sharing scheme: sharing, reconstruction, and weighted sums. this means that we could instead have used any other scheme with these properties and the

def share(secret, number_of_shares):

random_shares = [

sample_randomness(secret.shape)

for _ in range(number_of_shares - 1)

]

missing_share = (secret - sum(random_shares)) % Q

return [missing_share] + random_shares

def reconstruct(shares):

secret = sum(shares) % Q

return secret

def weighted_sum(shares, weights):

shares_as_matrix = np.stack(shares, axis=1)

return np.dot(shares_as_matrix, weights) % Q